Posted on behalf of Ortolf Harl. Translated from german original

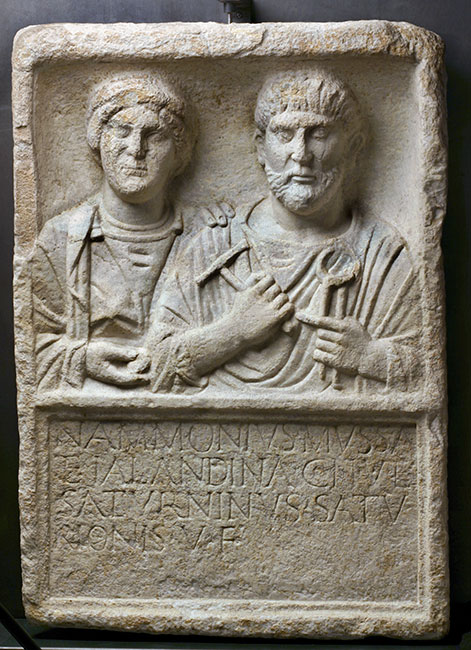

Grabmal des Nammonius Mussa

- Trismegistos-Id: n/a_PLUS::4122cb13c7a474c1976c9706ae36521d

- Material: stone / marble

- Artifact Type: inscription

- Type: porträtnische mit inschrift

- conservationPlace: Graz, Österreich

- findingSpotModern: Kalsdorf, Österreich

- entityType: artifact

- Repository: Ubi erat lupa

The simple monument from Kalsdorf in the region of Styria presents itself in an uncomplicated way: this inscription is to preserve the memory of Nammonius Mussa, to his wife Kalandina and Saturninus, son of Saturio. We hear nothing, however, about her parents and her age, neither on the profession of the man and the relationship in which Saturninus was to both. None of the persons has the three names as it is typical of Roman citizens. In the epigraphic database by Claus – Slaby (EDCS) Nammonii are attested almost only in the southeastern Noricum and in that area also Kalandinus or Kalandina have approximately the same distribution area as the one of the Nammonii. It could therefore be a ” local ” family whose members lived in the vici of the municipalities of Virunum and Flavia Solva.

- no response to http://gazetteer.dainst.org/search.json?q={%22bool%22:{%22must%22:%5B%20{%20%22match%22:%20{%20%22_id%22:%202089612%20}}%5D}}&type=extended!

#0 /var/www/html/eagle/wp-content/plugins/eagle-storytelling/esa_datasource.class.php(222): esa_datasource\abstract_datasource->_fetch_external_data('http://gazettee...') #1 /var/www/html/eagle/wp-content/plugins/eagle-storytelling/esa_datasource.class.php(207): esa_datasource\abstract_datasource->_generic_api_call('http://gazettee...') #2 /var/www/html/eagle/wp-content/plugins/eagle-storytelling/esa_item.class.php(142): esa_datasource\abstract_datasource->get('2089612') #3 /var/www/html/eagle/wp-content/plugins/eagle-storytelling/esa_item.class.php(63): esa_item->_generator() #4 /var/www/html/eagle/wp-content/plugins/eagle-storytelling/eagle-storytelling.php(703): esa_item->html(true) #5 /var/www/html/eagle/wp-includes/shortcodes.php(433): esa_shortcode(Array, '', 'esa') #6 [internal function]: do_shortcode_tag(Array) #7 /var/www/html/eagle/wp-includes/shortcodes.php(273): preg_replace_callback('/\\[(\\[?)(esa)(?...', 'do_shortcode_ta...', 'Posted on be...') #8 /var/www/html/eagle/wp-includes/class-wp-hook.php(324): do_shortcode('

Posted on be...') #9 /var/www/html/eagle/wp-includes/plugin.php(205): WP_Hook->apply_filters('

Posted on be...', Array) #10 /var/www/html/eagle/wp-includes/post-template.php(256): apply_filters('the_content', 'Posted on behal...') #11 /var/www/html/eagle/wp-content/plugins/eagle-storytelling-bridge/template/loop-single-story.php(38): the_content() #12 /var/www/html/eagle/wp-content/plugins/eagle-storytelling-bridge/template/single-story.php(9): include('/var/www/html/e...') #13 /var/www/html/eagle/wp-includes/template-loader.php(106): include('/var/www/html/e...') #14 /var/www/html/eagle/wp-blog-header.php(19): require_once('/var/www/html/e...') #15 /var/www/html/eagle/index.php(17): require('/var/www/html/e...') #16 {main}

We can get more information from the relief. First, the peculiar hierarchic differentiation of genres – womans to the rear, man in front. The identification of the names of the two people depicted is clear from the clothing. The woman has a woollen cap, tunic and brooches, as well as a cloak, as it is typical for South-West Noricum. The man with his hair style and a short beard is not a soldier, and certainly not a Roman citizen wearing a toga, but a craftsman in working clothes (tunic) with cape and tools. Hammer and tongs, which the Mussas ostentatiously put forward, grabs immediately the attention of the observer and when they where also coloured they must have been even more evident, in order to show him as a blacksmith. Due to their small size, we can also think he might have been a fine blacksmith.

At this point, we can try a little intellectual exercise: what if image and inscription had been separated by the coincidences of destruction so that we could no longer recognize the fact that they belonged together? Would we get the idea that Nammonius Mussa was a blacksmith? And vice versa, which was the name of the blacksmith pictured with his wife? In other words, image and inscription are inseparable, because they complement each other. Only when we read both artifacts together, the message reaches us completely.

But we are still missing a key aspect, namely the technical details of how it was set up, via lifting and dowel holes or clamps signs. In the present case it can be assumed that this front plate, only 20 cm thick, belonged to a composite tomb, made of several parts, a popular way of building tombs in Noricum. Therefore, one must mentally project lateral blocks that were probably also in relief, a base and a pyramidal or gable top, with which the monument may have been almost two meters high.

From the fact that “ordinary people” are depicted and that the inscription text is remarkably sparse, we can draw a far-reaching conclusion. Obviously, this is a secondary tomb which had its place in the grave of somebody with an higher social status, a full Roman citizen. The pater familias was surrounded by a colourful band, then came the real family members which where over freedmen – artisans, clerks, notaries, etc. and slaves. This all took place in the common grave for their final rest, gathered around the primary Tomb of the paterfamilias, who immortalized its social significance by the inscription, the image program and the architectural design of the monument. This means that the grave monuments were organized in a hierarchical as the members of the familia. If as the Blacksmith Nammonius Mussa you could already afford a relatively large secondary monument of marble, which was brought from far away, which dimensions must have had the primary monument of the pater familias?

This is the statement we can make about the grave in which our Nammonius Mussa was buried: he served a whole familia, was dominated by the towering and ornate primary monument of the pater familias, consisting of valuable stone material and expensive building. In secondary monuments was reflected the rest of the familia, organized according to relations and functions. All this expressed solidarity and economic power.

So, in general, we need to consider all aspects of a monument including the place of find as well as the part of the damage. In the Eastern Alps the stone monuments of the Romans faced a particularly difficult survival, because of the so-called “Völkerwanderung” and because of the Christianization. From Late Antiquity people carved metal of the joints out of the blocks and thus robbed the buildings their stability. After that, the church builder came and burned the high quality marble of the primary monuments to lime for walls, plastering and wall paintings. Usually, less expensive stones of the secondary monuments were used in the churches for gussets, buttresses, door and window frames etc. . This is why mainly stone monuments of the second and third level of quality remained, while we only have relatively few copies of the best quality ones – but we can admire these even more.

A holistic approach is therefore an important part of the Lupa (www.ubi-erat-lupa.org), in which all the stone monuments of a locality are treated equally and are available with a mouse click from various points.