In this “story” I would like to discuss a research idea that came to me while I was attending the EAGLE International Conference in Paris. I am not a specialist on the field, and what follows is just a series of notions and ideas I have developed ever since. I have always suspected that the EAGLE storytelling app could be a great environment for presenting ongoing research topics or questions; therefore, I will keep you posted about my ideas on the subject!

Nominal sentences

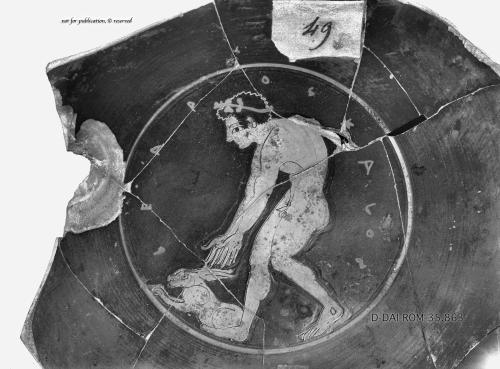

In my previous work on the syntax of ancient Greek poetry, I took some interest in what in Ancient Greek grammars is commonly referred to as the “nominal sentences”. Nominal sentences are those sentences where subjects and nominal predicates are joined without any verb that explicitly performs the function of “copula”. Sometimes, this construction is named “zero copula”. One famous example is the formula: “the boy [is] handsome” (ὁ παῖς καλός) that is often found inscribed on the Attic drinking cups or vessels, like this basin from Orvieto.

Red-figure basin from Ovieto. The inscription Λέαγρος καλός (“Leagros is handsome”) can be easily seen

“Zero-copula” constructions are fairly common around the world and, as Leon Stassen writes in the World Atlas of Linguistic Structures (WALS), the definition “zero copula” might seem misleading or even Eurocentric, by conveying the false impression that what is common on most modern European languages (i.e. that the function of joining subjects and nominal predicates is performed by a specific “copula” verb like “to be”) is the norm. The situation of the natural languages, instead, is very complex and cannot be reduced to a question as simple as “copula” vs “zero copula”. WALS, in any case, displays a very informative map of the languages that admit or don’t admit the nominal structure, while a great survey of the attested constructions, as well as a masterful interpretation of the data, is in this classic work of É. Benveniste.

In ancient Greek texts, especially poetry, nominal sentences are not at all infrequent, but the construction with the verb εἶναι performing the function of the copula is equally firmly attested. Very often, nominal sentences are explained as cases of verbal ellipsis, and it is fairly common in schools or in learner manuals to read that, in constructions like ὁ παῖς καλός, the verb “to be is implied”. This is incorrect; or to be precise, one has to distinguish true cases of ellipsis (as in clausal coordination, where the ellipsis is admitted even in a language that doesn’t allow zero copula like English: “John is tall, and his brother [is] short”) from the actual nominal sentences. The decisive difference is that in what we call “nominal sentences”, to quote from Benveniste’s work, the predicative function is not performed by a word that belongs to the class of verbs, not even one that is implied from the context. In this case, the notion of a lexical item (such as the verb “to be” or equivalents in the different languages) that is implied from the context is clearly a misleading one.

What about inscriptions?

Although in Greek the “zero-copula” constructions with predicate nominal have attracted much attention, as being arguably and by far the most frequent case of nominal sentences, it is not the only type of sentence where the predication is not carried by a verb.

Now, verbs are often omitted in inscriptions. In votive inscriptions, where the structure of the message inscribed evokes a dedicatory event of the form: “X dedicated the inscribed monument K to Y (as a form of Z)”, not only some of the actors involved in the event can be (and the inscribed monument almost always is) omitted, but even the verb expressing the event is left out; equally often, however, a verb such as ἀνέθηκε (dedicated.3SG.AOR) is used. A quick search using the new EAGLE search engine can provide a quick overlook on the situation. As an example of the omitted dedication verb among the countless possible instances, one may quote the following inscription of the 3rd century AD from Dacia.

Translation: “Aurelius Stephanus to the god Mithra as a thank offering”.

Inscription HD049511 from the EAGLE collection

Shall we talk about “ellipsis” of the verb? And in what sense? It is interesting to note that in the definition of εὐχαριστήριον in the authoritative Greek-English Lexicon of Liddell and Scott a comparable inscription is quoted and the gloss “sc. ἀνέθηκεν” is added. Shall we do the same and imply a well defined, often explicitly attested and somewhat formulaic lexical item to be supplied mentally to the text?

Well, I came up with something like an hypothesis about it, but I would require a lot of work on the data before I can discuss it!

Corpus-based approaches?

In the context of a project like EAGLE, questions such as the one raised above can also entail a supplementary question of methods. Are we now in the position to leverage the digital collections to attempt a systematic survey of the evidence such as those that are customary in current corpus linguistics? In other words, can we gather enough quantitative evidence to advance conclusions that can legitimately be considered as exhaustive?

When I was surveying the usage of the nominal sentence in Aeschylus, I could make use of the Ancient Greek Dependency Treebank, a corpus where the syntax of every sentence was annotated. Such a corpus can be easily interrogated to count and list all the passages where a predicate nominal is construed without a governing verb, vs. the cases where it is governed by the verb εἶναι. No such corpus exists for the inscriptions. How difficult would it be to collect a sufficient collection of data in digital format? And how representative would this be of our type of documents (the Greek inscriptions, or – more realistically – the Greek inscriptions within a certain time frame and in a certain area)?

These are all great research questions that one day I hope I will be able to see through…